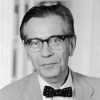

Richard Hofstadter

Richard Hofstadter

Richard Hofstadterwas an American historian and public intellectual of the mid-20th century. Hofstadter was the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History at Columbia University. Rejecting his earlier approach to history from the far left, in the 1950s he embraced consensus history, becoming the "iconic historian of postwar liberal consensus", largely because of his emphasis on ideas and political culture rather than the day-to-day doings of politicians. His influence is ongoing, as modern critics profess admiration for the grace of his...

NationalityAmerican

ProfessionHistorian

Date of Birth6 August 1916

CountryUnited States of America

Richard Hofstadter quotes about

The intellectual's ... playfulness, in its various manifestations, is likely to seem to most men a perverse luxury; in the United States the play of the mind is perhaps the only form of play that is not looked upon with the most tender indulgence. His piety is likely to seem nettlesome, if not actually dangerous. And neither quality is considered to contribute very much to the practical business of life.

To the zealot overcome by his piety and to the journeyman of ideas concerned only with his marketable mental skills, the beginning and end of ideas lies in their efficacy with respect to some goal external to intellectual processes.

It is the historic glory of the intellectual class of the West in modern times that, of all the classes which could be called in any sense privileged, it has shown the largest and most consistent concern for the well-being of the classes which lie below it in the social scale.

Anti-intellectualism ... has been present in some form and degree in most societies; in one it takes the form of the administering of hemlock, in another of town-and-gown riots, in another of censorship and regimentation, in still another of Congressional investigations.

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., in a mordant protest written soon after the [1952] election, found the intellectual "in a situation he has not known for a generation." After twenty years of Democratic rule, during which the intellectual had been in the main understood and respected, business had come back into power, bringing with it "the vulgarization which has been the almost invariable consequence of business supremacy.

The American farmer, whose holdings were not so extensive as those of the grandee nor so tiny as those of the peasant, whose psychology was Protestant and bourgeois, and whose politics were petty-capitalist rather than traditionalist, had no reason to share the social outlook of the rural classes of Europe. In Europe land was limited and dear, while labor was abundant and relatively cheap; in America the ratio between land and labor was inverted.

It has been our fate as a nation not to have ideologies but to be one.

It is a poor head that cannot find plausible reason for doing what the heart wants to do.

Intellect is neither practical nor impractical; it is extra-practical.

A university is not a service station. Neither is it a political society, nor a meeting place for political societies. With all its limitations and failures, and they are invariably many, it is the best and most benign side of our society insofar as that society aims to cherish the human mind.

In using the terms play and playfulness, I do not intend to suggest any lack of seriousness; quite the contrary. Anyone who has watched children, or adults, at play will recognize that there is no contradiction between play and seriousness, and that some forms of play induce a measure of grave concentration not so readily called forth by work.

Intellectualism, though by no means confined to doubters, is often the sole piety of the skeptic.

The role of third parties is to sting like a bee, then die.

There has always been in our national experience a type of mind which elevates hatred to a kind of creed; for this mind, group hatreds take a place in politics similar to the class struggle in some other modern societies.