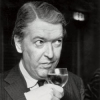

Kingsley Amis

Kingsley Amis

Sir Kingsley William Amis, CBEwas an English novelist, poet, critic, and teacher. He wrote more than 20 novels, six volumes of poetry, a memoir, various short stories, radio and television scripts, along with works of social and literary criticism. According to his biographer, Zachary Leader, Amis was "the finest English comic novelist of the second half of the twentieth century." He is the father of British novelist Martin Amis...

NationalityEnglish

ProfessionNovelist

Date of Birth16 April 1922

CityLondon, England

A German wine label is one of the things life's too short for.

[Science fiction is] that class of prose narrative treating of a situation that could not arise in the world we know, but which is hypothesised on the basis of some innovation in science or technology, or pseudo-science or pseudo-technology, whether human or extra-terrestrial in origin. It is distinguished from pure fantasy by its need to achieve verisimilitude and win the 'willing suspension of disbelief' through scientific plausibility.

He who truly believes he has a hangover has no hangover.

Be glad you're fifty - andThat you got there while things were nice,In a world worth looking at twice.So here's wishing you many more years,But not all that many. Cheers!

Man's love is of man's life a thing apart;Girls aren't like that.

To refer even in passing to unpublished or struggling authors and their problems is to put oneself at some risk, so I will say here and now that any unsolicited manuscripts or typescripts sent to me will be destroyed unread. You must make your way yourself. Why you should be so set on the nearly always disappointing profession is a puzzling question.

The Scandinavians are dear people but they've never been what you might call bywords for wit and sparkle, have they?

With some exceptions in science fiction and other genres I have small difficulty in avoiding anything that could be called American literature. I feel it is unnatural, not I think entirely because it uses a language that is not mine, however closely akin to my own.

I've been trying to write for as long as I can remember. But those first fifteen years didn't produce much of great interest. I mean, it embarrasses me very much to look back on my early poems--very few lines of any merit at all and lots of affectation. But there were quite a lot of them. That's a point in one's favor.

It's never pleasant to have one's unquestioning beliefs put in their historical context, as I know from experience, I can assure you.

The world that seemed so various and new, well, it does contract. One's burning desire to investigate human behavior, and to make, or imply, statements about it, does fall off. And so one does find that early works are full of energy and also full of vulgarity, crudity, and incompetence, and later works are more carefully finished, and in that sense better literary products. But . . . there's often a freshness that is missing in later works--for every gain there's a loss. I think it evens out in that way.

Feeling a tremendous rakehell, and not liking myself much for it, and feeling rather a good chap for not liking myself much for it, and not liking myself at all for feeling rather a good chap.

It is not extraordinary that the extraterrestrial origin of women was a recurrent theme of science fiction.

The human race has not devised any way of dissolving barriers, getting to know the other chap fast, breaking the ice, that is one-tenth as handy and efficient as letting you and the other chap, or chaps, cease to be totally sober at about the same rate in agreeable surroundings.