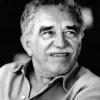

Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez; 6 March 1927 – 17 April 2014) was a Colombian novelist, short-story writer, screenwriter and journalist, known affectionately as Gabo or Gabito throughout Latin America. Considered one of the most significant authors of the 20th century and one of the best in the Spanish language, he was awarded the 1972 Neustadt International Prize for Literature and the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature. He pursued a self-directed education that resulted in his leaving law...

NationalityColombian

ProfessionNovelist

Date of Birth6 March 1927

CountryColombia

In her final years she would still recall the trip that, with the perverse lucidity of nostalgia, became more and more recent in her memory.

Tell him,' the colonel said, smiling, 'that a person doesn’t die when he should but when he can.

And again, as always, after so many years we were still in the same place we always were.

Carmelia Montiel, a twenty-year-old virgin, had just bathed in orange-blossom water and was strewing rosemary leaves on Pilar Ternera's bed when the shot rang out. Aureliano José had been destined to find with her the happiness that Amaranta had denied him, to have seven children, and to die in her arms of old age, but the bullet that entered his back and shattered his chest had been directed by a wrong interpretation of the cards.

The only thing he could do to stay alive was not to allow himself the anguish of that memory. He erased it from his mind, although from time to time in the years that were left to him he would feel it revive, with no warning and for no reason, like the sudden pang of an old scar.

In some way impossible to ascertain, after so many years of absense, Jose Arcadio was still an autumnal child, terribly sad and solitary.

It was the year they fell into devastating love. Neither one could do anything except think about the other, dream about the other, and wait for letters with the same impatience they felt when they answered them.

Most critics don't realize that a novel like One Hundred Years of Solitude is a bit of a joke, full of signals to close friends; and so, with some pre-ordained right to pontificate they take on the responsibility of decoding the book and risk making terrible fools of themselves.

People spend a lifetime thinking abouthow they would really like to live. I asked my friends and no one seems to know very clearly. To me, it's very clear now. I wish my life could have been like the years when I was writing 'Love in the Time of Cholera.'

Sex is the consolation you have when you can't have love.

Florentina Ariza had kept his answer ready for fifty-three years, seven months and eleven days and nights. 'Forever,' he said.

No matter what you do this year or in the next hundred, you will be dead forever.

She always had a headache, or it was too hot, always, or she pretended to be asleep, or she had her period again, her period, always her period. So much so that Dr. Urbino had dared to say in class, only for the relief of unburdening himself without confession, that after ten years of marriage women had their periods as often as threes times a week.

Over the years they both reached the same wise conclusion by different paths: it was not possible to live together in any other way, or love in any other way, and nothing in this world was more difficult than love.