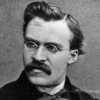

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzschewas a German philosopher, cultural critic, poet and Latin and Greek scholar whose work has exerted a profound influence on Western philosophy and modern intellectual history. He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest ever to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in 1869, at the age of 24. Nietzsche resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life, and...

NationalityGerman

ProfessionPhilosopher

Date of Birth15 October 1844

CityRocken, Germany

CountryGermany

Whatever we have words for, that we have already got beyond.

Where the good begins.- Where the poor power of the eye can no longer see the evil impulse as such because it has become too subtle, man posits the realm of goodness; and the feeling that we have now entered the realm of goodness excites all those impulses which had been threatened and limited by the evil impulses, like the feeling of security, of comfort, of benevolence. Hence, the duller the eye, the more extensive the good. Hence the eternal cheerfulness of the common people and of children. Hence the gloominess and grief - akin to a bad conscience - of the great thinkers.

It is, indeed, a fact that, in the midst of society and sociability every evil inclination has to place itself under such great restraint, don so many masks, lay itself so often on the procrustean bed of virtue, that one could well speak of a martyrdom of the evil man. In solitude all this falls away. He who is evil is at his most evil in solitude: which is where he is at his best - and thus to the eye of him who sees everywhere only a spectacle also at his most beautiful.

... hitherto we have been permitted to seek beauty only in the morally good - a fact which sufficiently accounts for our having found so little of it and having had to seek about for imaginary beauties without backbone! - As surely as the wicked enjoy a hundred kinds of happiness of which the virtuous have no inkling, so too they possess a hundred kinds of beauty; and many of them have not yet been discovered.

Suspicious.- To admit a belief merely because it is a custom - but that means to be dishonest, cowardly, lazy! - And so could dishonesty, cowardice and laziness be the preconditions for morality?

Whoever has overthrown an existing law of custom has always first been accounted a bad man: but when, as did happen, the law could not afterwards be reinstated and this fact was accepted, the predicate gradually changed; - history treats almost exclusively of these bad men who subsequently became good men!

Morality makes stupid.- Custom represents the experiences of men of earlier times as to what they supposed useful and harmful - but the sense for custom (morality) applies, not to these experiences as such, but to the age, the sanctity, the indiscussability of the custom. And so this feeling is a hindrance to the acquisition of new experiences and the correction of customs: that is to say, morality is a hindrance to the development of new and better customs: it makes stupid.

This demand follows from an insight that I was the first to articulate: that there are no moral facts.

For all things are baptized at the font of eternity, and beyond good and evil; good and evil themselves, however, are but intervening shadows and damp afflictions and passing clouds.

All names of good and evil are images; they do not speak out, they only hint. He is a fool who seeks knowledge from them.

All preachers of morality, as also all theologians have a bad habit in common: all of them try to persuade man that he is very ill, and that a severe, final, radical cure is necessary.

I do not mean to moralise but to those who do, I would give this advice : if you mean ultimately to deprive the best things and states of all all honour and worth then continue to talk about them as you have been doing!

In order for once to get a glimpse of our European morality from a distance, in order to compare it with other earlier or future moralities, one must do as the traveller who wants to know the height of the towers of a city: he leaves the city.

Socrates and Plato are right: whatever man does he always does well, that is, he does that which seems to him good (useful) according to the degree of his intellect, the particular standard of his reasonableness.