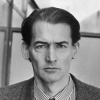

Rem Koolhaas

Rem Koolhaas

Remment Lucas "Rem" Koolhaasis a Dutch architect, architectural theorist, urbanist and Professor in Practice of Architecture and Urban Design at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University. Koolhaas studied at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London and at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Koolhaas is the founding partner of OMA, and of its research-oriented counterpart AMO based in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. In 2005, he co-founded Volume Magazine together with Mark Wigley and Ole Bouman...

NationalityDutch

ProfessionArchitect

Date of Birth17 November 1944

CityRotterdam, Netherlands