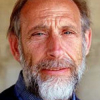

Leonard Susskind

Leonard Susskind

Leonard Susskind is the professor of theoretical physics at Stanford University, and director of the Stanford Institute for Theoretical Physics. His research interests include string theory, quantum field theory, quantum statistical mechanics and quantum cosmology. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences of the US, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, an associate member of the faculty of Canada's Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, and a distinguished professor of the Korea Institute for Advanced Study...

NationalityAmerican

ProfessionPhysicist

Date of Birth1 January 1940

CountryUnited States of America

I'm a great believer in our ability to come up with the ideas necessary to solve the big questions. I have less confidence that we'll be able to find a consensus about which ones are right without experiment.

I have a funny mental framework when I do physics. I create an imaginary audience in my head to explain things to - it is part of the way I think. For me, teaching and explaining, even to my imaginary audience, is part of the process.

Physics is perceived as a lonesome, nerdy kind of enterprise that has very little to do with human feelings and the things that excite people day-to-day about each other. Yet physicists in their own working environment are very social creatures.

I went to college because my father thought that I should learn engineering, because he wanted to go into the heating business with me. There, I realized I wanted to be a physicist. I had to tell him, which was a somewhat traumatic experience.

Extra dimensional theories are sometimes considered science fiction with equations. I think that's a wrong attitude. I think extra dimensions are with us, they are with us to stay, and they entered physics a long time ago. They are not going to go away.

Over the years, I began to understand that there were a lot of people out there reading physics in popular literature that they could not understand - not because it was too advanced, but because it wasn't advanced enough.

I'm a great believer that scientists should spend as much time as possible explaining, and you do explain in the process of teaching.

Why is there space rather than no space? Why is space three-dimensional? Why is space big? We have a lot of room to move around in. How come it's not tiny? We have no consensus about these things. We're still exploring them.

I'm doing physics because I'm curious about how it works - full speed ahead, damn the torpedoes, don't worry about whether somebody is going to be able to do an experiment next week, just figure it out.

It seems hopelessly improbable that any particular rules accidentally led to the miracle of intelligent life. Nevertheless, this is exactly what most physicists have believed: intelligent life is a purely serendipitous consequence of physical principles that have nothing to do with our own existence.

I have always enjoyed explaining physics. In fact it's more than just enjoyment: I need to explain physics.

I'm not going to argue with people about the existence of God. I have not the vaguest idea of whether the universe was created by an intelligence.

You are a victim of your own neural architecture which doesn't permit you to imagine anything outside of three dimensions. Even two dimensions. People know they can't visualise four or five dimensions, but they think they can close their eyes and see two dimensions. But they can't.

Space can vibrate, space can fluctuate, space can be quantum mechanical, but what the devil is it? And, you know, everybody has their own idea about what it is, but there's no coherent final consensus on why there is space.