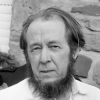

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn was a Russian novelist, historian, and short story writer. He was an outspoken critic of the Soviet Union and its totalitarianism and helped to raise global awareness of its Gulag forced labor camp system. He was allowed to publish only one work in the Soviet Union, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, in the periodical Novy Mir. After this he had to publish in the West, most notably Cancer Ward, August 1914, and The Gulag...

NationalityRussian

ProfessionNovelist

Date of Birth11 December 1918

CityKislovodsk, Russia

CountryRussian Federation

When I returned to Russia in 1994, the Western world and its states were practically being worshipped. Admittedly, this was caused not so much by real knowledge or a conscious choice, but by the natural disgust with the Bolshevik regime and its anti-Western propaganda.

When the whole discussion of "developing a national idea" hastily began in post-Soviet Russia, I tried to pour cold water on it with the objection that, after all the devastating losses we had experienced, it would be quite sufficient to have just one task: the preservation of a dying people.

When Russia started to regain some of its strength as an economy and as a state, the West's reaction - perhaps a subconscious one, based on erstwhile fears - was panic.

If we look far into the future, one can see a time in the 21st century when both Europe and the USA will be in dire need of Russia as an ally.

Today when we say the West we are already referring to the West and to Russia. We could use the word 'modernity' if we exclude Africa, and the Islamic world, and partially China.

For us in Russia, communism is a dead dog, while, for many people in the West, it is still a living lion.

The Gulag Archipelago, 'he informed an incredulous world that the blood-maddened Jewish terrorists had murdered sixty-six million victims in Russia from 1918 to 1957! Solzhenitsyn cited Cheka Order No. 10, issued on January 8, 1921: 'To intensify the repression of the bourgeoisie.'

What would things been like [in Russia] if during periods of mass arrests people had not simply sat there, paling with terror at every bang on the downstairs door and at every step on the staircase, but understood they had nothing to lose and had boldly set up in the downstairs hall an ambush of half a dozen people?

As for Europe, its claims towards Russia are fairly transparently based on fears about energy, unjustified fears at that.

A great disaster had befallen Russia: Men have forgotten God; that's why all this has happened.

For us in Russia communism is a dead dog. For many people in the West, it is still a living lion.

I have not painted the dark reality in rose-tinted shades but I do include a clear way, a search for something brighter, some way out - most importantly in the spiritual sense.

The demands of internal growth are incomparably more important to us... than the need for any external expansion of our power.

When I was young, the early death of my father cast a shadow over me - and I was afraid to die before all my literary plans came true. But between 30 and 40 years of age my attitude to death became quite calm and balanced. I feel it is a natural, but no means the final, milestone of one's existence.